- Technical debt, a term first coined by Ward Cunningham, is not unlike financial debt: It refers to the practice of making coding or design decisions to expedite production or gain other short-term benefits, knowing that these decisions may require corrections later.

- Typically, technical debt results when developers take shortcuts that enable them to quickly deliver features or functionality to keep up with customer demand. This might mean being first to market, responding to time-critical customer needs, and/or improving performance and value.

- Technical debt can also accrue because a product’s technology or architecture no longer scales and needs refactoring.

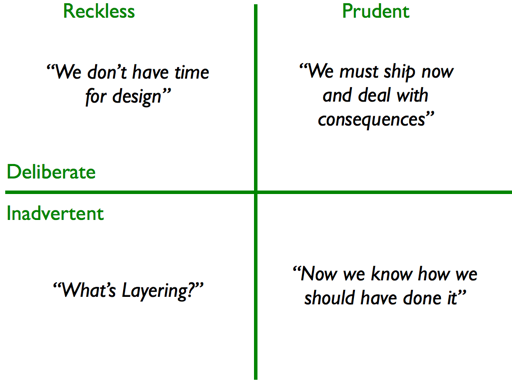

- Sometimes it accrues because it is invisible or inadvertent, as shown in this technical debt quadrant.

-

Left untracked, technical debt can quickly become difficult to manage, or even to recognize.

-

Often it becomes such a burden that it prevents developers from making consistent progress on critical business needs.

-

Still, taking on technical debt is not necessarily a bad thing, as long as you recognize that you are taking it on and understand that the debt needs to be paid down. Sometimes it makes sense to take a coding shortcut if it helps you get to market sooner or be more responsive to your customers’ needs.

-

Often, the benefits outweigh the costs of taking on technical debt. The ability to get customer feedback quickly is critical, for example. But if a feature that was rushed doesn’t meet customer needs, refactoring is irrelevant because the feature will be deprecated or little-used. On the other hand, if the feature proves to be valuable and heavily used, it should be a candidate for refactoring, or paying down that debt.

- Flow velocity decreases: Flow velocity gauges whether value delivery is accelerating. It represents the number of work items completed over a specific time period, which enables you to measure throughput. As such, a decrease in flow velocity is an important sign that intervention may be needed.

- Flow time increases: Flow time can identify when time to value is getting longer. It measures the time it takes for work items to go from “work start” to “work complete,” including both active and wait times. This allows you to measure time-to-market for the desired throughput to ensure that it is fast enough for the short feedback cycles needed when dealing with uncertainty. When flow time increases, organizations can’t respond fast enough to business needs.

- Quality decreases as the code base becomes more fragile: Quality can be measured in several different ways, but the most common is the number of production incidents your customers experience. A decrease in quality should never be ignored.

- Costs increase: Costs include all those associated with the product, including people resources, infrastructure, and license costs. An increase in costs should be addressed promptly to ensure your company can remain competitive.

- Technical debt must be kept within certain limits to avoid hurting the business. Unpaid technical debt generates interest that increases over time and adds to the cost of fixing the problem. Carrying too much technical debt leads to negative business (versus IT) consequences, including:

- Lost sales and/or lower productivity due to system outages.

- A loss of competitive advantage due to a progressively poorer user experience.

- An inability to adapt to market changes.

- Fines due to security breaches.

- Poor decisions resulting from inconsistent or untimely data.

- You can’t fix what you can’t measure. Before you can pay back technical debt, you must first measure the current state of work (e.g., technical debt, customer feature work, addressing defects, and managing security/risk issues).

- Correlating the impact of tech debt with value-adding work can help your business understand its danger on the bottom line. Set aside time and resources every financial year to tackle technical debt, as it can accumulate because of a lack of funding and sponsorship.

- When developers take shortcuts, it’s a good practice to create technical debt work items as a reminder that this debt work needs to be paid back.

- Making this visible as a work item, along with features, defects, and risk, is key to ensuring it can be prioritized appropriately and given the resources required. As a rule of thumb, some teams set aside 20 percent of their bandwidth to ensure that debt gets paid off.

- There are several different ways you can contextualize technical debt–from using everyday analogies, such as the importance of daily household upkeep, to the benefits of preventative maintenance, as in the classic Fram oil filter “pay me now or pay me later” commercials. You can also leverage compelling visuals like the one below to dramatize your arguments.

- Measure technical debt ratio: First, figure out where you stand. Tools such as SonarQube and Coverity can help you measure technical debt and determine your technical debt ratio (TDR), which is the ratio of the cost to fix the software system vs. the cost to build it.

- The TDR is important as it tells you how long it might take to convert problematic code into quality code.

- Determine payback time: Next, IT and business should look at trends that determine an appropriate level for when to pay back debt. Like any business that maintains a healthy level of debt on its books, IT and the business need to understand the right level of technical debt for their situation. This may vary from company to company, product to product, and even team to team. It involves determining how much capacity to allocate to debt until the metrics (flow velocity, flow time, and quality) improve to produce the desired business results.

- Prioritize debt: Finally, determine which debt is most important to address in terms of what will improve productivity, reduce flow time, and improve quality. Focus on the highest-priority items first, utilizing the capacity determined in the previous step.

- Tracking and measuring technical debt may seem cumbersome, but left unmonitored, technical debt will gradually impact the flow of value to customer-facing products. Ensure that technical debt is visible and measured so that the business and IT can team up to proactively tackle and manage technical debt. This will help you maintain a healthy product portfolio that can sustain your business.'

- Technical debt impacts the whole company, but it especially affects engineers as more tech debt means more bugs, performance issues, downtime, slow delivery, lack of predictability in sprints, and therefore less time to work on new exciting projects.

- Engineers waste seven hours per week on technical debt which is often invisible to stakeholders. Speaking to non-technical stakeholders using business terms is the best way to make technical debt easily seen.

- Mess isn’t always bad, just as technical debt doesn’t always mean there’s a problem. The key is to fix the right amount of technical debt at the right time.

- Companies should aim to proactively and continuously address technical debt. Continuously addressing technical debt gives teams an opportunity to deliver value regularly and empowers engineers to make decisions.

- In the future, technical debt will become less of an engineering problem and more of an important business prerequisite that helps with delivering more value to our customers and the business.

- Prioritise transparency with technical debt. Transparency, says Wolpers, makes managing technical debt much simpler. He recommends that teams prominently display a visualisation of their technical debt to keep it at as a front-of-mind priority and that they review their tech debt needs during every Sprint meeting.

- Track tech debt. Wolpers suggests counting bugs and using more in-depth code metrics like cyclomatic complexity, code coverage, SQALE-rating, and rule violations if possible.

- Pay back debt quickly and regularly. Like financial debt, technical debt is best managed when teams pay back their loans on a regular basis. Wolpers says that Scrum teams should consider allocating 15-20 percent of their resources to refactoring code and fixing bugs every sprint cycle.

- Align product backlog. Your product backlog should include tasks related to paying back technical debt. Organising your debt into what you want to tackle this sprint will help keep the debt from falling through the cracks and being forgotten about.

- Adjust your definition of “done.” Don’t count something as finished until it meets a set standard for manageable tech debt. Standardise procedures. Develop a repeatable formula for how your team handles adding experiments or new features that include the introduction of technical debt.

- Intentional tech debt (also called deliberate or active) occurs when organisations choose to leave room for improvement in their code for the sake of reducing time-to-market.

- Unintentional tech debt (also called accidental, outdated, passive, or inadvertent) happens when the code quality needs improvement after a period of time. This could be the result of poor production the first time around or simply the natural need for updates as code becomes outdated.

- Architecture Debt

- Build Debt

- Code Debt

- Defect Debt

- Design Debt

- Documentation Debt

- Infrastructure Debt

- People Debt

- Process Debt

- Requirement Debt

- Service Debt

- Test Automation Debt

- Test Debt

At the very least, software developers should be counting and keeping track of their bugs. This includes both fixed and unfixed bugs.

Noting the unfixed bug allows development teams to focus on and fix them during their Agile iterations. Noting the fixed bugs helps teams measure how effective their tech debt management process is.

While bugs have a more direct effect on the software’s end-users, code complexity can really damage the development team and the organization as a whole.

Look for code complexity metrics like…

- Cyclomatic complexity

- Class coupling

- Lines of code

- Depth of Inheritance

- The lower each of these measures, the better.

Keeping an eye on these metrics also helps organisations know exactly which code to rework or refactor in order to reduce complexity and improve the backend side of the software.

Like code quality, focusing specifically on code cohesion will help the code from getting too complex. A high code cohesion usually means that the code is more maintainable, reusable, and robust. It also minimises the amount of people who need to get involved in the code, which can greatly reduce complexity and decrease the chances of bit rot.

High cohesion is when you have a class that does a well defined job.

More engineers usually means more cruft, and more cruft often leads to greater problems and higher levels of unintentional technical debt. That’s why code ownership is such a valuable metric: it answers the question, “who is focusing on what code?” If something breaks, who do you call?

This metric will give your project management eyes on the amount of people working on various pieces of code. Knowing this information will enable these teams to reduce the amount of people and time dedicated to these efforts. You don’t want one person owning a complete section of code - just in case they get ran over by a bus or, in a better scenario, a new job. Usually, the right level is for teams of engineers to own domains in the codebase.

Code 'churns' when it gets rewritten / replaced. It's a measure of the activity a given piece of code sees. You want to give special attention to code that sees a lot of activity because any problem in there will be exacerbated. Measuring churn, then, helps teams recognise and prioritise what parts of the code require refactoring. If engineers have to constantly address bugs around the same part of the code, that means something is going wrong over there. Watching for that churn will help organisations pinpoint those problems more quickly, allowing them to fix the problem with a permanent solution that keeps tech debt down.

Keeping track of these tech debt metrics will not eliminate all your debt, but it will help you manage it more effectively.